Are you having a tough time making good decisions in your career? Leading in the face of constant change is tough. Especially in this age of COVID-19, uncertainty is our norm. Being prepared in the face of uncertainty is necessary amidst the struggles of the national pandemic. Today, we will discuss some tips to help you decide with confidence in the face of ambiguity.

Making Mental Space

When we have too many decisions to make all at once, we tend to either shoot from the hip or over-analyze. Neither approach leads to the desired outcome. When we clear our minds of the clutter, we create the mental space to make a few high-quality decisions.

The first step that you can take towards this outcome is to not waste energy muddling over the thousands of tiny low consequence decisions that take up our brains. Just knock those projects out and move on to bigger things.

For the higher-stakes decisions, focus on the handful of most important items and remove the rest by asking yourself some questions:

-

- Do I have to make this decision, or is this something I can delegate? Being the leader doesn’t mean you have to have all the answers. Ask your team or colleagues to define the question, assess good options, and recommend and execute the decisions. Learning how to delegate can challenge, but it is a skill worth learning.

- If I do not decide today, will it go away? What if you just sat on the issue for a while? Sometimes the problem just goes away on its own. There are many tools for understanding this tactic out there. Find one that works best for you!

- Is the issue something I must decide on my own, or can we decide as a group? Group decisions take more time, but get better results and generate support (or buy-in). Ask the team (or form a group) to share the decision-making process.

Admit Your Blind Spots

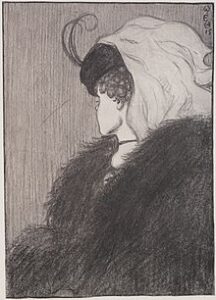

When I first saw this picture, I was 100% certain it was an old woman in profile, with a protruding chin and nose. The drawing is of an old woman, but it’s also a picture of a young woman, turned away, sporting a necklace. Even after a friend showed me the lines intersecting to form the neck, nose, and eyelash, I still couldn’t see the young woman in the picture.

We see with our own unique frames — mental constructs that we use to simplify the things we find complex — that come from our experiences, values, and cultural background. These frames filter how we see our contextual reality. Once you see something a certain way, it’s tough to see it differently.

If we don’t recognize these personal filters, our frames can create problems. The result is that we make snap judgments and gather evidence to support that view, irrelevant as to whether or not it is accurate. We can also define a challenge too narrowly, from our singular perspectives, and end up deciding on a limited solution—overlooking better potential options.

Denying our biased frames can lead to having an overconfident view of ourselves. We might think that we know it all because of that bias. Good decision-making requires an understanding of our frames and knowing the limits of our knowledge. The variables that we need to consider when making decisions can be discovered when we question–(1) what we know, (2) what others know that we don’t, and (3) what no one can know. Questioning ourselves in this way means admitting the level of uncertainty we’re dealing with in decision-making and preparing to be wrong.

Fall in Love with the Problem

When faced with a challenge, we tend to ask too narrow of a question that drives “this or that” options and other binary options. For example, if I’m hungry after dinner, I could ask myself whether I would like to have cake or ice-cream for dessert. A better question to ask would be “how might I satisfy or prevent after-dinner-hungers?” That question opens up a world of choices, from considering other types of desserts to adjusting the time that I will eat, or even having a bigger dinner.

Fall in love with the problem, before you settle on either-or choices. A few simple ways that you can do that are by:

- Asking others with different perspectives on how they see the challenge. Ask “what am I missing?” or “what’s another way of looking at this?”

- Looking at the issues below the surface. The root causes may be the actual problem that needs to be solved.

- Phrasing a question in a way that does not contain a solution in it is a way that is broad enough to generate lots of options but narrow enough to be practical.

Once you settle on a broad question, generate the right options using these steps:

- Create clear criteria—the attributes that any solution suggested with must meet.

- Diverge before you converge—brainstorm many options before you settle on a small group of options and then compare the few decided on side-by-side to see what might be doable.

- Gather representative evidence to form options. Beware of classic mistakes at this step, such as over-reliance on the evidence that’s easiest to get. Another is paying too much attention to the most recent piece of data you’ve seen; or hyper-focusing on only one piece of evidence.

- Figure out what your known unknowns are, and how you’ll address these.

- Surface the assumptions and limits of knowledge, and rate the level of confidence in any assertions.

- Balance your biases by inviting counterarguments and disconfirming questions. Always have a trusted Devil’s Advocate on hand to challenge you!

Don’t keep collecting data, hoping the answer will magically appear. Especially during this tough time, there’s often more than one right answer. Do as Colin Powell and Jeff Bezos do, and shoot for 70% of the information necessary to proceed.

Make sure you converge on some vastly different options. You will know you’re on the right track if there’s lots of disagreement!

Assess, Test, Decide

When assessing your options, be honest about the uncertainty and estimate your confidence levels. Consider the average experience of people who have tried something similar rather than the most successful examples and determine what one can reasonably expect. Consider the surface assumptions and the effects that they might have on the outcome.

Where the situation is relatively predictable and you have relevant expertise, it’s fine to go with your gut. As the uncertainty increases, so should your level of analytical rigor—starting with a qualitative assessment. You can use the rules of thumb. For example, using threshold rules with pre-set criteria to rule out choices, such as a hurdle rate for capital investment. Another great option is the good old-fashioned pros and cons list. You can weigh your decision-making criteria in terms of its thoroughness. More complicated assessment options include computer models, simulations, and scenario planning.

Where there is a lot of uncertainty, it is better to test than it is to predict. Prototype your options, test them (with end-users where applicable) and learn what will work as you go. You can use this approach not just for testing products and services, but also for building partnerships and creating strategies.

Prepare to Fail

Once you settle on a decision, it’s wise to think through all the things that could go wrong because it probably will. If you have already surfaced assumptions and risks related to your options, you’re well ahead of the game!

There are many things that you can do to prepare:

- Prepare for the most-successful and least-successful scenario.

- Write a list of risks and determine how you will mitigate them.

- Give yourself a “safety factor.” This will give you some wiggle room that can buffer errors in your projections.

- Set “trip-wires,” or signals that will alert you when you are off-track before it is too late.

- Fail fast or set up experiments to test your assumptions, take you too far out of the way.

Another great tool here is the “premortem.” This is when you imagine that the plan plays out and your project has failed. You can then identify all the things that went wrong with the project. Though it all is occurring inside of your imagination, it is amazing how this future-thinking allows you to see some things you might not have already noticed by identifying risks. After you have jotted down “all the things that went wrong,” note how likely it would be that the outcome you imagined would happen and what the consequences might be for each option that you might choose.

There are so many free resources that might help you master the ability of good decision-making. If you are still struggling with this skill, consult a coach that can guide you to your goal.

Jessica McGlyn

Catalytics.com